Why Does Canada Have a Strategic Maple Syrup Reserve?

On Friday, news broke that thieves had stolen $30 million dollars worth of Quebec's strategic maple syrup reserves. Much as the United States keeps a stock of extra oil buried in underground salt caverns to use in case of a geopolitical emergency, the Federation of Quebec Maple Syrup Producers has been managing warehouses full of surplus sweetener since 2000. The crooks seem to have made off with more than a quarter of the province's backup supply. (I personally suspect these guys.)

Why exactly does Canada need to stockpile syrup? To find out, I called up Michael Farrell, an extension associate at Cornell University's College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, and an expert in all things maple.

"We think of it as a little cottage industry here in the states," he told me. "But up there [syrup is] a big industry that's responsible for a lot of people's livelihoods."

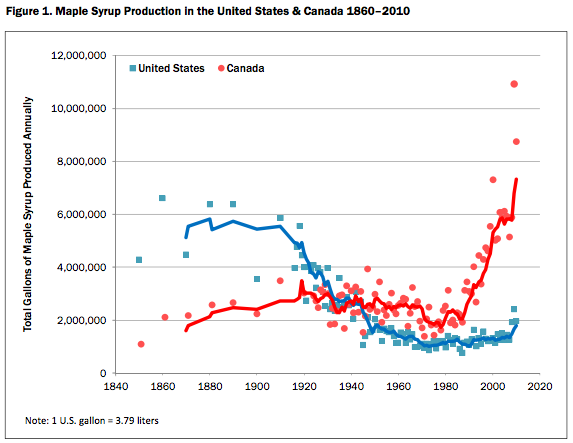

Canada took over from the United States as the world's leader in syrup in the 1940s, as shown in this graph from a paper Farrell co-authored last year. Today, Quebec taps 75 percent of the world's supply, and its producers have been attempting to grow their market abroad. Shipments to Japan, for instance, rose 252 percent between 2000 and 2005.

But harvesting maple is a fickle business, and that makes expanding the industry tricky. The trees need cold nights and mildly warm days to yield sap, meaning production can vary greatly year to year based on the weather. That's a potential problem for the big syrup buyers, whether they're bottlers or large food companies that make cookies or cereal. Quaker can't pour a bunch of time and money into developing a maple-and-brown-sugar-flavored version of Life, only to find out it won't be able to get enough of its ingredients, or that they'll have to pay through the nose for each liter of syrup.

"If you are trying to develop a market for something, you don't want to create a demand and not be able to supply it," Farrell said.

The reserve makes sure there's always enough syrup for the market. As Farrell explained, each producer sells its harvest in bulk to the federation -- a government-sanctioned cooperative -- which turns around and deals it to bulk buyers. When production is high, the federation siphons a portion off to store in steel drums for future use.

Not long ago, Farrell said, the maple industry found out just what kind of calamity could ensue when if stockpile ran out. In the early aughts, the government began opening new forest areas to maple production. To keep the additional supply from cratering prices, Quebec's federation introduced a quota system. Unfortunately, that limited reserves, which ran dry after three years of weak harvests. In 2008, supplies of syrup ran short and prices jumped from around $2.40 per pound to $4.00. It was a short-term windfall for producers that had the potential to do long-term damage as buyers were priced out of the market, Farrell said. In response, the federation nixed its quotas in order to rebuild its surplus.

So who on earth would want to raid the reserves? Farrell offered me one theory, which seemed reasonable enough.

"It's got to be an inside job," he said. "What do you do with that much syrup? You have to be in the industry."